Night Dude and the Second Society Take on the Forces of Chaos Following Revolution

August 2014

The Road Less Traveled

By Tamar Donovan

As soon as we moved into our new home in Cairo, we learned that a fact of life in the city was the presence in apartment and office buildings of a class of worker known as bowabs, or porters. Bowabs were expected to collect trash from residents’ front doors, sweep and mop the stairwells and lobby, escort meter readers and delivery men, and generally keep an eye on the building’s comings and goings.

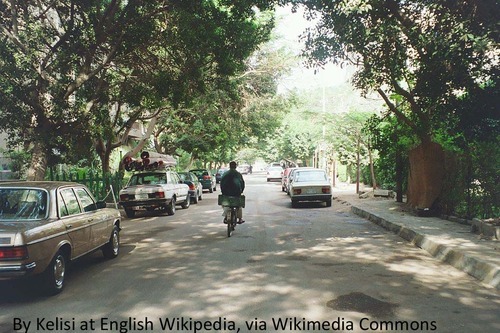

The bowabs in our building lived in a plain, tiny apartment with threadbare furnishings; they were a young and fluid population, groups of two and three boys at a time coming to try life in the big city and returning to the village when it got to be too much. Other bowabs on our street lived with their wives and children in tiny spaces carved out of lobbies and parking garages. I called the porters and gardeners and sweepers, this population that served our wealthy neighborhood with so few hopes of advancement, the Second Society.

At some point, we noticed that there was another person working on our street. He showed up every evening and slept in a worn wooden booth. He did this “to watch the street,” because, in his opinion, the troika of policemen who sat catty-corner to his booth were not up to the task.

We became accustomed to seeing him arrive around dusk, spread out his rug for prayers, have a good gossip with the policemen, and then settle in his booth for the night. We called him Night Dude. My husband became aware at a certain point that he was expected to pay Night Dude for his extra service watching our street.

In time, Night Dude began to wash our car in the mornings and water our garden; he also kept us aware of each other’s movements (“Mister is out.” “Madame is at the club.”). Our children stopped to greet him on their way to and fro. My husband and Night Dude, whose given name was Rahim, often spent time talking in the early morning, when Night Dude was ending his working day and my husband was beginning his.

Night Dude had his own names for us, too. We were very confused when he began addressing our youngest son, Victor, as Doctor. We accepted this quirk without question, however, answering as politely as ever when, on our evening walks, he emerged from his booth to greet us. As our knowledge of our environment deepened, we realized that he had gone to the trouble to research the Egyptian Arabic equivalents of our sons’ names. These carried millennia of meaning from Coptic and Egyptian history but were far from their modern, American English variants. Night Dude had been calling our son Boctor, the ancient Coptic form of Victor.

When it was time to pay the bowabs and Night Dude on the first of each month, the subject of his salary came up for discussion. “You realize you are overpaying him tremendously,” I would say unfailingly to my husband as I prepared the pay envelope. Night Dude had stepped up on his own to help with the little bits of work that made our life more pleasant, but I am sure that the wife, six children, daughter-in-law, and grandchild living under Night Dude’s roof also had something to do with my husband’s calculation of the monthly “salary.”

We had arrived in Cairo in the summer of 2008 and these were some of the smaller details of our daily life for two and a half years. Then, on January 25, 2011, the Arab Spring came to Egypt. On January 28, we awakened to find that we had no internet; our cell phones were also useless. My husband left immediately for the U.S. Embassy, which was situated next to Tahrir Square, the center of the Egyptian Revolution. I understood when he left that he would be staying at work round-the-clock until the situation in Tahrir calmed, whenever that might be.

By the next night, most of our neighbors had disappeared, as had the policemen on the corner – in fact, the police had disappeared from every corner in the city. There were rumors of a massive prison break not far from our neighborhood, rumors of home invasions, rumors of looting. We heard gunfire outside night and day. At night, only one other apartment on our block had lights in the windows. There was a curfew in place from late afternoon to early morning, and we were told that violators could be shot on sight.

I stepped out on the balcony with my oldest son that second evening and saw that the bowabs of our street had come out in force. They had put up barricades on either end of the street from whatever spare materials they could find; one young guy in a dusty brown galabeya from two houses over patrolled our block with an iron bar across his shoulders. We had begun to hear that some of the violence in the city might have been perpetrated by people settling old scores, taking advantage of the vacuum left when the police withdrew from the streets. I definitely had the feeling, watching the young man stride jauntily up and down our street with his chin held high, that some were just eager for the release they believed a good fight would give them.

The three boys and I had spent the night before crammed onto the floor in the safe haven room of our apartment, listening to gunfire. Just as we were retreating to the apartment for another sleepless night, one of my sons spotted Night Dude approaching our corner. He had come to watch the street. His booth had been appropriated to serve as a barricade, but no mind. He took his spot in a row of chairs with the bowabs from across the street and they settled in for a long night of civil defense. My eyes filled with tears. Night Dude had risked arrest or worse in breaking the curfew to come to us. We would not be alone.

That was how we spent our last few nights in Cairo as we waited for evacuation orders, just us and the Second Society on our otherwise abandoned street. The children and I did not return to Cairo, but my husband stayed behind to finish out the assignment. We were able to see him for a few minutes and say good-bye only because he was at the airport assisting with the evacuation.

After we left, I worried about Night Dude. Who would overpay him when my husband was gone? Our oldest son returned to Cairo to visit friends just this year. He found Night Dude in place in his corner booth, which, he reports, is now sporting a Diplomatic Security sticker, one that my husband gave him. And among ourselves, we continue to use the Egyptian Arabic names that Night Dude bestowed on us in those peaceful, warm Cairo evenings that we love to remember. In this way, we still hear his voice.

© 2014 by Tamar Donovan. All rights reserved.

Tamar Donovan is a librarian, information architect, freelance writer, and accompanying spouse of a Diplomatic Security Special Agent for the U.S. Department of State. She, her husband, and their three sons have served in Kyiv, Ankara, Vladivostok, Tashkent, Cairo, and most recently Moscow. Her fiction and non-fiction have appeared in The Baltimore Sun, Happy, Tales from a Small Planet, and the anthology Freedom’s Just Another Word.